Etymologically, the word ‘glamour’ originates from the Old Scottish ‘gramarye’, suggesting magic, necromancy and other occult doctrines. English historians R. Buckley and E. de la Hay define glamour in a sociocultural sense as an artificially constructed image of reality, a call to consumption, signifying an affinity with the generally accepted standards of luxury.

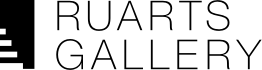

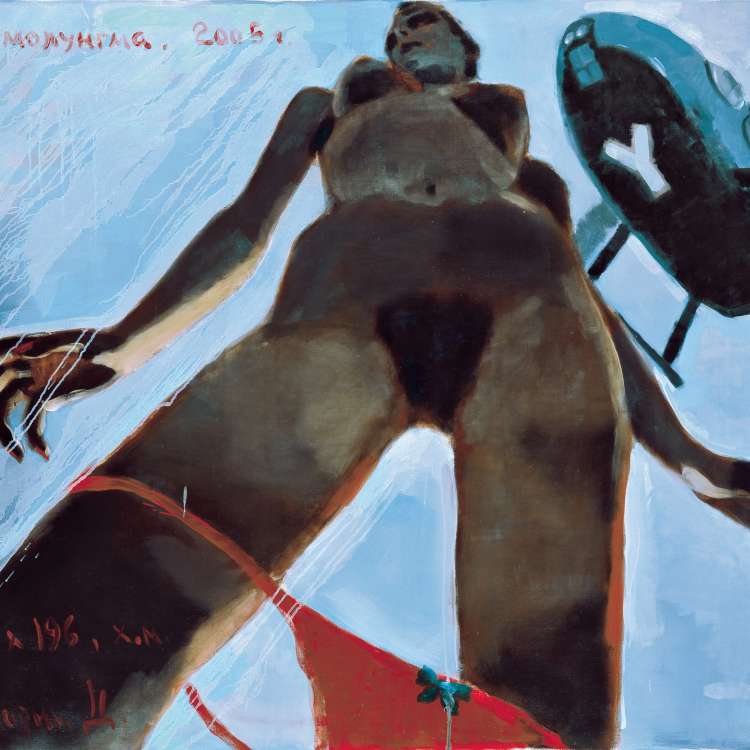

‘Trash’ is easy to define in simple terms: garbage, that which goes against the generally accepted standards of good taste, something made hastily without respect for material or subject matter. Trash sets itself against ‘glossy’ advertising and, as a rule, appeals primarily to intellectuals. In itself, trash-art is not bad or insignificant art. The appeal of trash-art is partially explainable due to its brutal energy and its unpredictability.

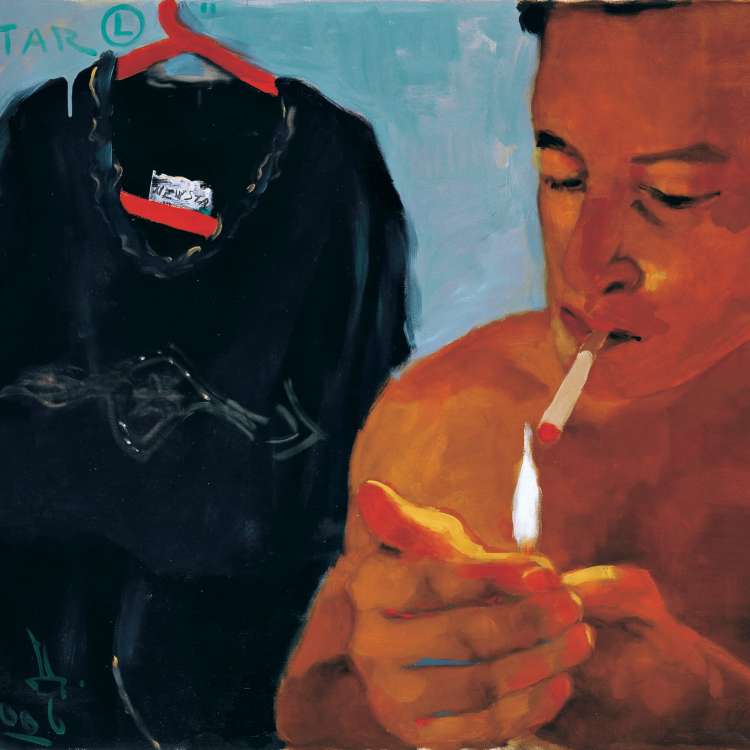

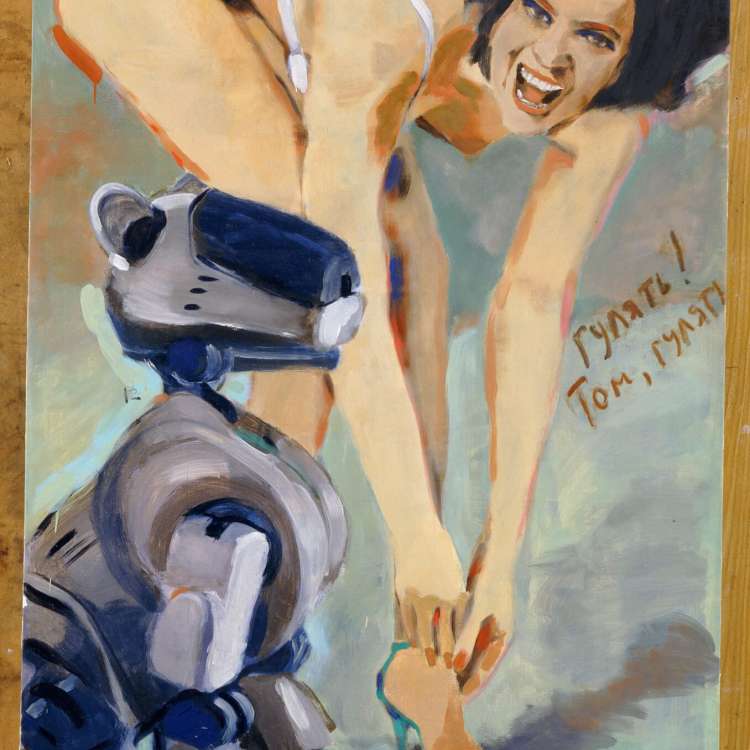

The interaction of trash and glamour leads to a conflict between their opposing identities and ultimately the deconstruction of the latter. Glamour acquires the features inherent in trash: awkwardness, aggression, insignificance, while at the same time, trash makes free use of the aesthetic qualities of glamour, using them to mock and sabotage it.

Having originated among the mass media of the last quarter of the previous century, trash and glamour have quickly turned to codes of visual culture. This is why it is no surprise at all to see the appearance of their hybrid, trash-glamour, appearing in actual art. Its imagery is borrowed from photographic or cinematic content, which characterizes it as nonpicturesque aestheticism.

The search for and collection of everyday materials and their subsequent representation by the artist in biographic or confessional form is already irrelevant in contemporary artistic life. For a change, there is now a healthy interest in photography and media, which gives rise to the production of trash-glamour.